Georgia Kerby, Exhibitions Curator

At the moment the nights are cooler and they are darker earlier. People are hunkering down at home with wooly socks and heaters. It is the time when the shortest day of the year- the winter solstice- is approaching. In the Southern Hemisphere this occurs on the 21st June.

In the Māori calendar this is the new year- Matariki- marking the changing of seasons. In Nga Puhi tradition the star Puanga (or Rigel in the Orion constellation) becomes visible above the eastern horizon in June and heralds the new year, which arrives with the next full moon. Puanga’s seven sisters Matariki also become visible around this time.

Now fires are lit, and everybody comes together to share in feasts, games, stories, song, and dance. After the solstice we can look forward to the coming year, where kai moana and whenua abound.

The Māori year has 12 or 13 months, depending on location, and is measured by the moon’s cycle. Regular movements of the moon and stars match seasonal changes in the natural world and act as guides for when certain activities should be carried out. For example, the blooming of Puawānanga (White Clematis) signals the time to begin springtime food gathering activities like eeling.

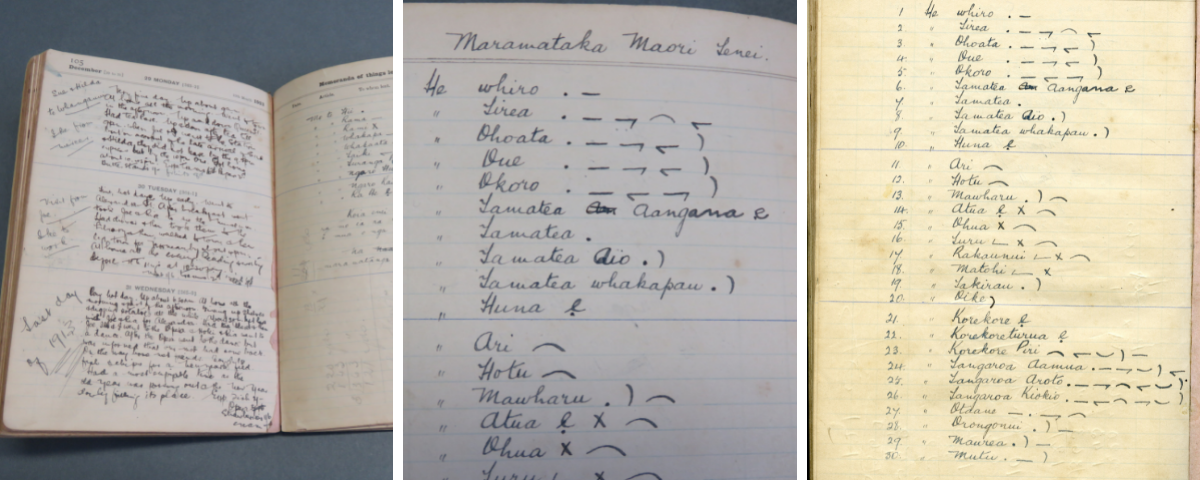

The maramataka or traditional lunar calendar guides such activities in greater detail, based on each night of the month. Whangārei Museum is the caretaker for a very special taonga, an original maramataka, handwritten in te reo Māori by Ihaka te Tai. In 1965, five of Ihaka’s diaries were donated to the Museum by Mr G. Bartlett, who was the Headmaster of Rawhiti School from 1912 to 1923. Mr. Bartlett was a friend of Ihaka and helped him get the job of Rawhiti Post Master.

Before this, Ihaka te Tai was a blacksmith at the Auckland Railway Workshops. He wrote these diaries during this time, from 1913 to 1914. The te Tai family are from Rawhiti in the Bay of Islands. In the 1913 diary Ihaka mentions the death of his father Mita te Tai and his burial near Rawhiti.

A handwritten maramataka such as this version is very rare. A statement written at the bottom of Ihaka’s maramataka suggests that his calendar was provided by Nuutana Mapi in 1902. Nuutani came from the Ohaewai area. The few recorded maramataka’s from this period vary slightly depending on the part of the country they are sourced from, making this calendar significant as one of the few Northland records.

Historian Elsdon Best published an identical calendar in his 1929 Fishing Methods and Devices of the Maori and 1922 The Maori Division of Time., quoting his source as Reverend Metara te Ao-marere of Ōtaki. Best mentions that Metara received his information from Mita te Tai, Ihaka’s father. In Ihaka’s diary, he records a visit from “Iehu Metara” and his family in August 1914. This may be the same Metara.

So, it appears that Best’s famous maramataka was sourced from Reverend Metara, who sourced his from Mita te Tai, who in turn possibly sourced his from Nuutana Mapi. The passing on of such knowledge indicates it’s importance to everyday life as a useful tool to regulate regionally relevant, seasonal activities. In this sequence it is not clear how many written versions there would have been, but fortunately for Northland one has been preserved at the Museum.

Most maramataka record the names for the lunar phase of the 29 or 30 nights in a month. Some recorded by Best include notes about specific weather or fishing or hunting activities. Ihaka’s calendar includes symbols for each night to represent the certain kinds of fishing that could take place during that lunar phase. For example, the night of the new moon Whiro is good for both fishing by torchlight (black dot) and line fishing (black line); whereas the tenth night Huna is always unlucky.

Ihaka’s diary had been entered for nearly every day of the year 1913. Each day is filled with tiny script using a mixture of te reo Māori and English, noting the weather, the day’s main activities and visitors. His first entry records “Ra tuatahi o te tau 1913”: the first day of the year- “Up around 8.30am. Had a service – hymns. Reading & writing all day…as soon as the clock struck twelve we had the piano going, the mob started to sign songs, piano duet, oh! We did have a time. Guns were going off- the bell was ringing…”. While Ihaka was based in Parnell, Auckland, for most of this time, his diary records many trips around Northland and names many local people, creating an important record of everyday life in Northland in the early 1900s.

Ihaka te Tai’s diary and maramataka are on display at Whangārei Museum over the Matariki period. Join our Matariki Dawn event at Kiwi North at 6 am on Saturday the 19th June to celebrate the new year with breakfast, a fire, and learning about the stars at Planetarium North.