With the advent of cellphones and other smart devices to arrange off-the-cuff visits to friends and family, carte de visite (visiting cards) have virtually lost their use. Several boxes of such cards in Whangarei Museum’s Archives are personal ephemera of bygone times and bygone rules.

Possibly originating in China in the 15th century AD, visiting or calling cards rose in worldwide use in the 17th century AD. Preceding our modern technology, people used small pre-cut pieces of card to pre-announce their arrival at someone’s home or to leave a note if their intended were out. Within the growing rigidity and extravagance of social etiquette during French King Louis XIV’s reign, visiting cards became a fundamental marker of social interaction within high society.

Europeans and Americans of the 18th and 19th centuries used visiting cards within a serious social structure. Traditional rules guided the approach, timing and expected reciprocity of social visits. Primarily used in the middle and upper classes, the exchange of carte de visite generally relied on the presence of servants. Guests had to present their card to a servant in the parlour, before being accepted in by the lady of the house. It was all in the detail, for example folding over a corner indicated that the card owner was there in person, folding in the middle said that it was meant for the whole family. Although, the height of rudeness to look at someone’s pile of visitor cards, people often displayed the cards of their most prestigious guests for other visitors to glimpse.

Many cultural practices were transported to New Zealand along with new settlers in the mid-nineteenth century. A box of Goodall & Sons plain white cards in Whangarei Museum record the names of Whangarei residents such as Roger Lupton in neat ink calligraphy. Mr. Lupton spent many years teaching at schools in the UK and fruit growing in America before he moved to New Zealand and became the first headmaster at Whangarei High School. His visiting cards likely date to around 1900, probably bought in a store in Auckland with other specialty goods imported from Britain. We hold his desk within the Whangarei Museum collection.

Goodall & Sons was founded by Charles Goodall in Soho, London, in 1820. Joined by his two sons, the company expanded into new factories and they became one of the world’s leading card makers. Printed playing cards were their specialty, but they expanded with other products like fortune, note and greeting cards. At the turn of the 20th century, around 75% of the United Kingdom’s playing cards were produced in the Goodall & Sons Camden factory. With no further family to succeed the business, the company merged with competitor De La Rue in 1922.

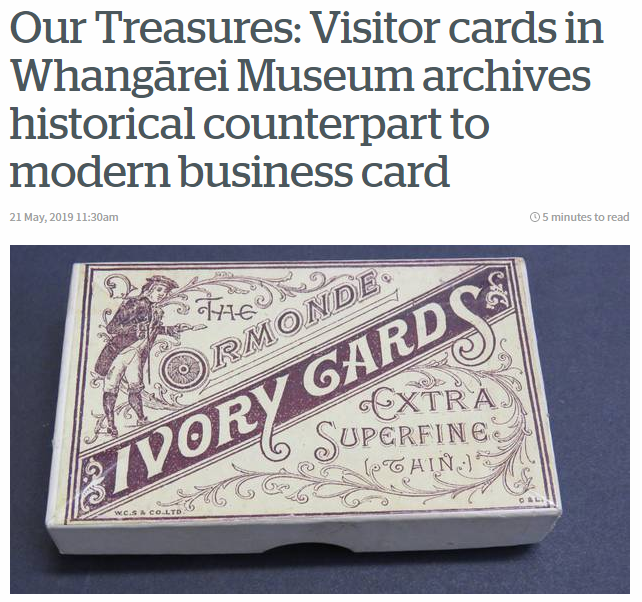

Another cardboard container in Whangarei Museum is of the Victorian brand Ormonde “Ivory Cards Extra Superfine (thin) visiting cards”. Inside is a small leather backed pad of ivory coloured visiting papers. Rather than the pre-printed variety this pad was more versatile and could be used by anyone in any situation, as long as they had a writing instrument.

While early 18th century cards were often decorated with family coat of arms, cards were most lavishly decorated in the later Victorian era. Many became artworks in themselves, advanced by the development of colour lithography printing methods. Victorian ladies often decorated theirs with poems or flowers, using the language of flowers to convey messages. Instead of the colourful and flowery ‘visiting cards’, businesses used ‘trade cards’. These simply presented business details and directions for potential customers or partners. A new group of entrepreneurial businessmen developed what became the modern business card during the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 19th century. Many of the upper class remained snobs to the use of business cards instead of personal visiting cards, but evidently these early form of business cards gained favour and became the modern counterparts of visiting cards.

Visiting cards were part of a complex system of etiquette, something which we still practice in many forms but are much less conscious of. In New Zealand nowadays, business cards have virtually no formality; thrown around at business events as an easy way of passing on contact details. Around the world, business cards are held in much higher regard. They reflect a personal or company brand. Original visiting cards were similar; if presented neatly and with the proper protocol they upheld the reputation of the owner and hopefully sparked the interest and respect of the receivers. Choices in card quality, colours and text font are matters of pride and identity, overstated in the famous business card scene in the movie American Psycho.

We are now seeing an increasing audacity and creativity in business card design to reflect the qualities of the brand or product they are advertising. However, the plain white card with black ink prevails, preserving quality and simple functionality, just like the Whangarei Museum’s historical counterparts.

Georgia Kerby

Curator | Kiwi North